Project Statement

The Venezuelan state of Vargas has been the epicenter of recurrent natural disasters as a result of uninformed planning and a combination of deliberate and spontaneous urban development. The geographic reality of the ecosystem has systematically been overlooked, putting over 75% of the population at risk.

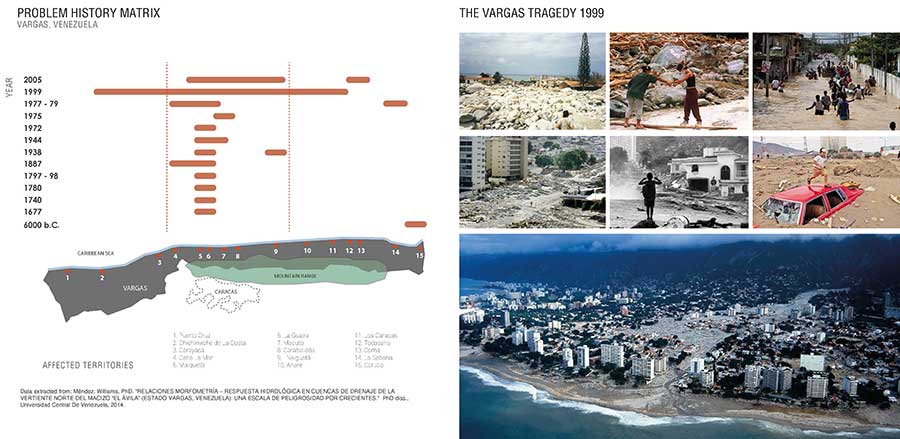

The last occurring event is known as The Vargas Tragedy of 1999, one of the greatest catastrophes of 20th century Latin America. This mudslide impacted 23 cities and resulted in enormous damages to infrastructure, the disappearance of historical and cultural referents, as well as significant human losses.

Parque del Recuerdo focused on the generation of ecological and social resilience through landscape design and the safeguarding of memory. The proposed Master Plans transform the watercourses from a threat to green corridors that protect and connect the city while enhancing biodiversity. Additionally it intends to promote transformation in the community by creating awareness and providing them tools to understand and alter their reality, preventing future tragedies.

Project Location

Project Location

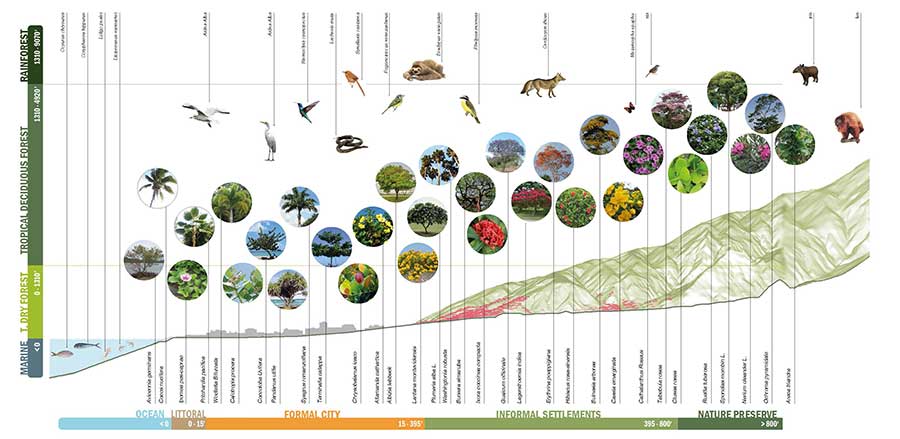

Vargas state is one of Venezuela’s most important coastal areas. It is comprised of a wide range of natural ecosystems ascending from its littoral edge to a mountain range that culminates in El Ávila National Park.

The state of Vargas is one of Venezuela’s most important coastal areas, flanked by a mountain range to the south and the warm waters of the Caribbean to the north. These shores comprise a 108-mile-long stretch of coastline ranging from 6 to 50 miles wide. Vargas, with its 11 municipalities, is home to the nation’s principal airport and shipping port, in addition to historically serving as the recreational epicenter of Caracas, Venezuela´s capital city. The coastline is comprised of a wide range of natural ecosystems ascending from its littoral edge to a mountain range that culminates in El Ávila national park. Because of these proximities and abundant natural resources, the area holds tremendous potential to become a key destination for Caribbean tourism.

Geographically, the area is made up of numerous rivers and streams composing basins and sub-basins of varying widths capable of collecting an exceedingly high volume of water. Subjected to intense levels of precipitation during the rainy season, these watercourses, accelerated by the steep topography, produce violent discharges of water flow, which creates dangerous conditions for local populations. Travelling at high speed, the water is capable of causing dramatic damage to the narrow coastline, damaging the ecosystems, settlements, and infrastructure in its wake.

Vulnerability of the Region

Vulnerability of the Region

“The Vargas Tragedy” was the latest of recurrent mudslides caused by large amounts of runoff flowing from the range towards the sea at high speeds given the steep slopes of the mountain and the narrow condition of the coast.

Regional Context and Social Analysis

The city of Caraballeda was selected as a case study within Vargas due to its complex natural and built environment, serving as a model for replication at the state level. Additionally, Caraballeda experienced the highest death toll after the tragedy.

A large portion of the population lives along these water channels and little has been done to manage the risk of these recurrent events. Since 1677, records confirm their occurrence once every 50 years on average. The most recent materialized in 1999. Known as “The Vargas Tragedy,” it devastated 23 cities in one of the greatest catastrophes of the 20th century in Latin America, resulting in incalculable damages to infrastructure, the disappearance of historical and cultural references, and the largest death toll ever recorded by a mudslide event in the world.

Urban development, both planned and unplanned, has since ignored this geographic reality, destabilizing the area and increasing the vulnerability of its inhabitants. The most populated areas within these cities reside within high or moderate risk zones, threatening an average 75% of their populations. In addition to the physical devastation, catastrophes such as the Vargas tragedy also impact the collective memory of a society. The destruction of a territory, disappearance of structures, and the displacement of inhabitants create tangible and intangible wounds. How can cultivating collective memory about natural disasters help diminish the vulnerability of a society? Can it help avoid these historical patterns from repeating themselves?

Habitat and Vulnerability Analysis

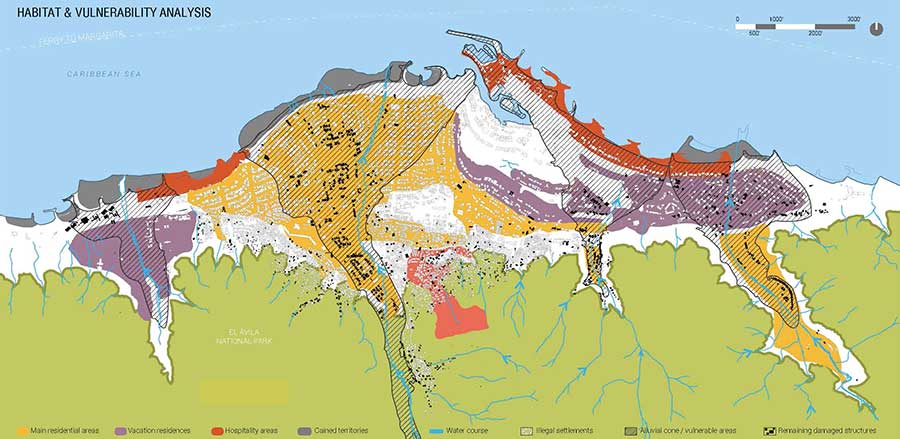

Regulated by the 1973 ordinance, Caraballeda’s main residential areas are located on the alluvial cones of the rivers. The presence of unplanned self-built dwellings along these riverbanks increases the vulnerability of the population. 75% of Caraballeda’s inhabitants live at risk.

Boundaries and Edges Analysis

Caraballeda is a highly fragmented city divided by three rivers crossing transversally. Settlements have developed around the watercourses as product of human instinct and government guidelines. For example, informally built dwellings along these riverbanks exacerbate the vulnerability of the region.

Urban Master Plan and Zoning

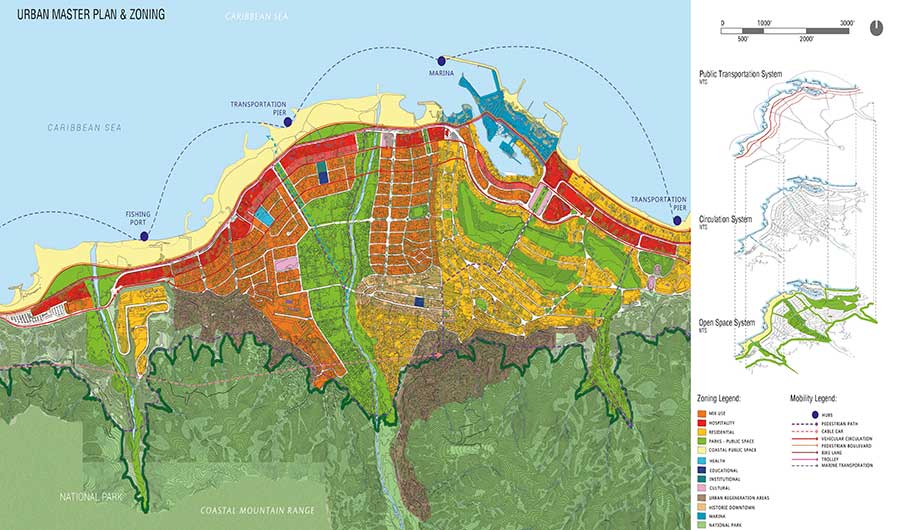

The urban Masterplan focused on relocation of residential areas, increase of urban connectivity, and revealing the possibilities hidden below the scars of previous mudslides. Most importantly, it considered the possibility of replication in other cities.

The vision behind Parque del Recuerdo is to heal these wounded cities by transforming their physical and social reality through landscape and developing a model that can be replicated throughout the region. The watercourses become the focus for these resilient landscapes. The goal of the plan is to create urban and social resilience by creating physical connections, restoring natural habitats, promoting sustainable and low impact tourism, establishing seasonal wetlands, and healing through public space.

The city of Caraballeda was selected within Vargas because of its complex natural and built environment. As the third most important city in the state, it experienced the highest death toll after the tragedy. It is also the fastest growing population in Vargas. With over 50,000 inhabitants, Caraballeda is a highly fragmented city divided by three rivers crossing transversally. Settlements have developed around the watercourses, both as product of human instinct and government guidelines. In 1999, Caraballeda was regulated by a 1973 ordinance, which designated the main residential areas inside the alluvial cones of the rivers. Exacerbating the vulnerability of the region is the presence of informally built dwellings along these riverbanks.

Replicability Potential

The transformation of the physical and social reality of the region can be replicated following Caraballeda’s model. The watercourses that flow from the mountain range into the Caribbean Sea become the central focus for these resilient landscapes.

Parque del Recuerdo

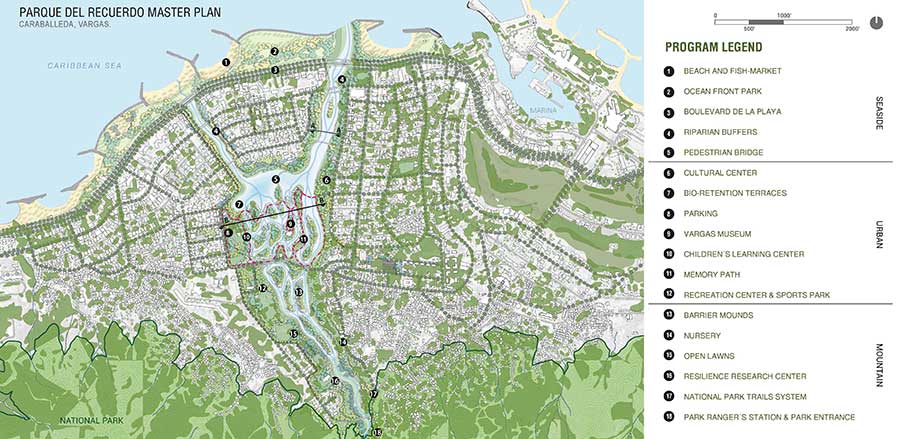

This 176-acre park translates the scars of the tragedy by transforming the existing channelized watercourse into a sinuous riparian corridor, creating a complex system of floodable areas and barrier mounds that act as a protection mechanism and provides public space.

The need for ease of evacuation brings up another critical concern. According to census data, 65% of the population depends exclusively on public transportation to move around the city, but only one transversal connection through the city exists. The main state road, running parallel to the shore, is the only way to cross the rivers and enter or exit the city, making everyday mobility and emergency evacuation incredibly challenging.

With an integral approach, the design process begins by analyzing the social, cultural, historical, and ecological reality of the region in order to develop an urban master plan for Caraballeda, applying strategies that allow for its replicability in other cities in Vargas. The plan aims to relocate the main residential areas, increase urban connectivity, protect watercourses, create an open space system, and memorialize the scars of the Vargas tragedy. The primary goal is to introduce a mitigation forest that reduces the potential impact of recurring mudslide events and opens the city up towards its river, creating spaces for public participation that go a step further than disaster recovery.

The masterplan envisions a 176-acre park that translates the scars of the tragedy by transforming the existing channelized watercourse into a sinuous riparian corridor, creating a complex system of floodable areas and barrier mounds that act as a protection mechanism to dissipate the energy of water flows. The plan is divided into three areas: Seaside, Urban and Mountain. Underutilized vacant land, comprised of damaged buildings and illegally occupied lots for industrial purposes, is repurposed as a network of restored native plant and wildlife communities. A series of recreational open spaces are organized to create a diversity of opportunities for outdoor learning and recreation.

Plant Selection

Plant Selection

Plants were selected according to their ecosystems and their soil stabilization qualities. The deep-rooted species are placed on the barrier islands to slow down the flow by creating friction and dissipating energy.

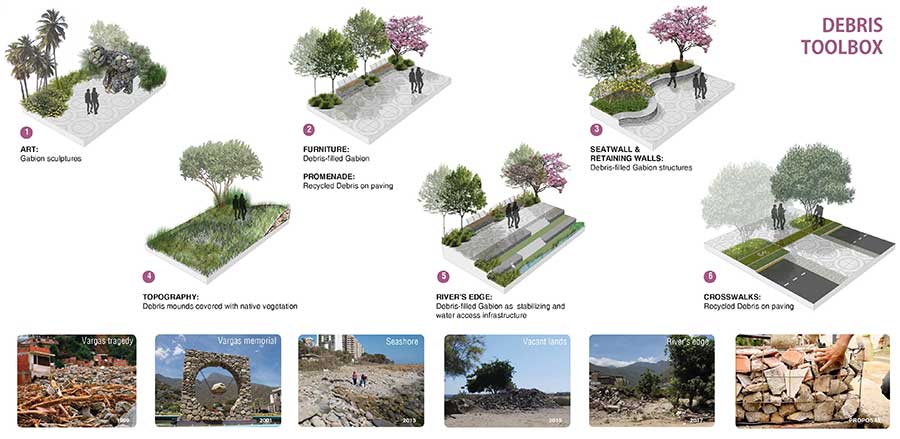

Debris Toolbox

Debris Toolbox

Debris is the main local material as a byproduct of the disaster. The toolbox was developed to involve the affected community, creating awareness and education opportunities on sustainable and accessible strategies for rebuilding efforts.

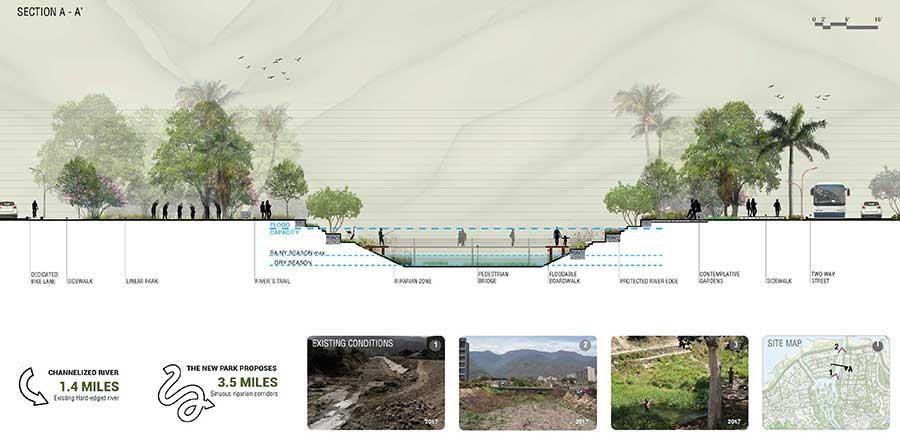

Section A-A’

Section A-A’

City resilience is enhanced through habitat restoration, economic and social activation, and a strong circulation system using the river as a corridor to connect the sea to the mountain and establishing transversal connections.

The Mountain proposal concentrates on nature preservation, settlement control inside the national park, and immersive experiences. The Urban strategy focuses on habitat restoration, social reactivation, and a strong circulation system. The river is managed as a corridor able to connect the sea to the mountain range and establish transversal connections at multiple points to enhance the city’s resilience. The Seaside strategy focuses on economic reactivation, supporting hospitality services and promoting tourism. The boundary between urban development and natural areas are blurred as this green corridor extends across neighborhoods with programs like a fish market, the Vargas museum, and a children’s learning center. Resilience can be achieved from the perspective of learning to live with nature instead of resisting it. This also means learning to live with the memory of natural disaster instead of erasing it. How can collective memory shape post-disaster redevelopment?

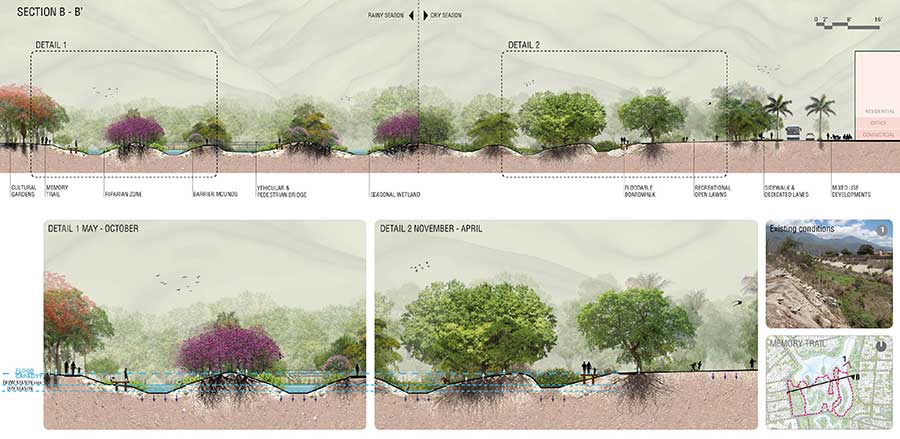

The Memory Trail, at the core of the park, promotes the assimilation of the disaster itself, its antecedents and consequences, to give inhabitants the opportunity to reconcile with their circumstances. Places of remembrance are fundamental to the reconstruction of post-disaster areas and act as reference points for what was lost as a result of the event. The Memory Trail is dedicated to serving this purpose, using the landscape to create awareness in the community about their reality. Vegetation welcomes the rain with blooms serving as a visual reminder and tribute to all who are no longer amongst us.

Recycling also becomes an instrument for remembrance. Debris is the main local material, a byproduct of the disaster, and can be reused in the construction of public spaces. A Debris Toolbox to clear and rebuild public space can be implemented through workshops where the affected community acts as the workforce to rebuild their own reality using easy and accessible building methods. This provides environmental and economic benefits by helping conserve natural resources, as well as decreasing the cost of both acquisition of new materials and disposal of debris.

Section B-B’

Section B-B’

A transversal section through the park shows the natural riparian buffer around the river and how the permeable surfaces were maximized to increase percolation. The landscape design considered both rainy and dry season flow patterns, in addition to extreme conditions.

A shift in paradigm

A shift in paradigm

While the blooming becomes an announcement of the rainy season it also represents a tribute to all who are no longer amongst us. By preserving and enhancing that memory it could be possible to heal trough landscape.

Parque del Recuerdo addresses the deficit of recreational spaces and lack of infrastructure after a devastating event, becoming a place that promotes community exchange amongst its inhabitants simply for the sake of it: the fundamental basis of coexistence and fraternity. This project serves to foster dialogue between citizens and honor the wounds that make up this harsh part of their history, while creating ecological and social resilience in a region that faces a constant threat of natural hazards. By revealing the possibilities hidden below the scars of the recurring mudslide events, and applying informed and conscious planning, it becomes possible to heal through landscape.

Press info:

Patricia Matamoros

pmata005@fiu.edu